Pharaoh

| Pharaoh of Egypt | |

|---|---|

| |

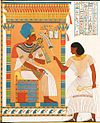

A typical depiction of a pharaoh usually depicted the king wearing the nemes headdress, a false beard, and an ornate shendyt (kilt) (after Djoser of the Third Dynasty) | |

| Details | |

| Style | Five-name titulary |

| First monarch |

|

| Last monarch |

|

| Formation |

|

| Abolition |

|

| Residence | Varies by era |

| Appointer | Hereditary |

| ||

| pr-ˤ3 "Great house" in hieroglyphs | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| nswt-bjt "King of Upper and Lower Egypt" in hieroglyphs | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pharaoh (/ˈfɛəroʊ/, US also /ˈfeɪ.roʊ/;[4] Egyptian: pr ꜥꜣ;[note 1] Coptic: ⲡⲣ̄ⲣⲟ, romanized: Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: פַּרְעֹה Parʿō)[5] is the vernacular term often used for the monarchs of ancient Egypt, who ruled from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BCE) until the annexation of Egypt by the Roman Republic in 30 BCE.[6] However, regardless of gender, "king" was the term used most frequently by the ancient Egyptians for their monarchs through the middle of the Eighteenth Dynasty during the New Kingdom. The earliest confirmed instances of "pharaoh" used contemporaneously for a ruler were a letter to Akhenaten (reigned c. 1353–1336 BCE) or an inscription possibly referring to Thutmose III (c. 1479–1425 BCE).

In the early dynasties, ancient Egyptian kings had as many as three titles: the Horus, the Sedge and Bee (nswt-bjtj), and the Two Ladies or Nebty (nbtj) name.[7] The Golden Horus and the nomen and prenomen titles were added later.[8]

In Egyptian society, religion was central to everyday life. One of the roles of the king was as an intermediary between the deities and the people. The king thus was deputised for the deities in a role that was both as civil and religious administrator. The king owned all of the land in Egypt, enacted laws, collected taxes, and served as commander-in-chief of the military.[9] Religiously, the king officiated over religious ceremonies and chose the sites of new temples. The king was responsible for maintaining Maat (mꜣꜥt), or cosmic order, balance, and justice, and part of this included going to war when necessary to defend the country or attacking others when it was believed that this would contribute to Maat, such as to obtain resources.[10]

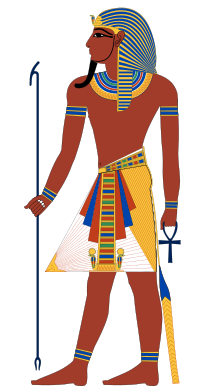

During the early days prior to the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, the Deshret or the "Red Crown", was a representation of the kingdom of Lower Egypt,[11] while the Hedjet, the "White Crown", was worn by the kings of Upper Egypt.[12] After the unification of both kingdoms, the Pschent, the combination of both the red and white crowns became the official crown of the pharaoh.[13] With time new headdresses were introduced during different dynasties such as the Khat, Nemes, Atef, Hemhem crown, and Khepresh. At times, a combination of these headdresses or crowns worn together was depicted.

Etymology

The word pharaoh ultimately derives from the Egyptian compound pr ꜥꜣ, */ˌpaɾuwˈʕaʀ/ "great house", written with the two biliteral hieroglyphs pr "house" and ꜥꜣ "column", here meaning "great" or "high". It was the title of the royal palace and was used only in larger phrases such as smr pr-ꜥꜣ "Courtier of the High House", with specific reference to the buildings of the court or palace.[14] From the Twelfth Dynasty onward, the word appears in a wish formula "Great House, May it Live, Prosper, and be in Health", but again only with reference to the royal palace and not a person.

Sometime during the era of the New Kingdom, pharaoh became the form of address for a person who was king. The earliest confirmed instance where pr ꜥꜣ is used specifically to address the ruler is in a letter to the eighteenth dynasty king, Akhenaten (reigned c. 1353–1336 BCE), that is addressed to "Great House, L, W, H, the Lord".[15][16] However, there is a possibility that the title pr ꜥꜣ first might have been applied personally to Thutmose III (c. 1479–1425 BCE), depending on whether an inscription on the Temple of Armant may be confirmed to refer to that king.[17] During the Eighteenth dynasty (sixteenth to fourteenth centuries BCE) the title pharaoh was employed as a reverential designation of the ruler. About the late Twenty-first Dynasty (tenth century BCE), however, instead of being used alone and originally just for the palace, it began to be added to the other titles before the name of the king, and from the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty (eighth to seventh centuries BCE, during the declining Third Intermediate Period) it was, at least in ordinary use, the only epithet prefixed to the royal appellative.[18]

From the Nineteenth dynasty onward pr-ꜥꜣ on its own, was used as regularly as ḥm, "Majesty".[19] The term, therefore, evolved from a word specifically referring to a building to a respectful designation for the ruler presiding in that building, particularly by the time of the Twenty-Second Dynasty and Twenty-third Dynasty.[citation needed]

The first dated appearance of the title "pharaoh" being attached to a ruler's name occurs in Year 17 of Siamun (tenth century BCE) on a fragment from the Karnak Priestly Annals, a religious document. Here, an induction of an individual to the Amun priesthood is dated specifically to the reign of "Pharaoh Siamun".[20] This new practice was continued under his successor, Psusennes II, and the subsequent kings of the twenty-second dynasty. For instance, the Large Dakhla stela is specifically dated to Year 5 of king "Pharaoh Shoshenq, beloved of Amun", whom all Egyptologists concur was Shoshenq I—the founder of the Twenty-second Dynasty—including Alan Gardiner in his original 1933 publication of this stela.[21] Shoshenq I was the second successor of Siamun. Meanwhile, the traditional custom of referring to the sovereign as, pr-ˤ3, continued in official Egyptian narratives.[citation needed]

The title is reconstructed to have been pronounced *[parʕoʔ] in the Late Egyptian language, from which the Greek historian Herodotus derived the name of one of the Egyptian kings, Koinē Greek: Φερων.[22] In the Hebrew Bible, the title also occurs as Hebrew: פרעה [parʕoːh];[23] from that, in the Septuagint, Koinē Greek: φαραώ, romanized: pharaō, and then in Late Latin pharaō, both -n stem nouns. The Qur'an likewise spells it Arabic: فرعون firʿawn with n (here, always referring to the one evil king in the Book of Exodus story, by contrast to the good king in surah Yusuf's story). The Arabic combines the original ayin from Egyptian along with the -n ending from Greek.

In English, the term was at first spelled "Pharao", but the translators for the King James Bible revived "Pharaoh" with "h" from the Hebrew. Meanwhile, in Egypt, *[par-ʕoʔ] evolved into Sahidic Coptic ⲡⲣ̅ⲣⲟ pərro and then ərro by rebracketing p- as the definite article "the" (from ancient Egyptian pꜣ).[24]

Other notable epithets are nswt, translated to "king"; ḥm, "Majesty"; jty for "monarch or sovereign"; nb for "lord";[19][note 2] and ḥqꜣ for "ruler".

Functions

As a central figure of the state, the pharaoh was the obligatory intermediary between the gods and humans. To the former, he ensured the proper performance of rituals in the temples; to the latter, he guaranteed agricultural prosperity, the defense of the territory and impartial justice.

In the sanctuaries, the image of the sovereign is omnipresent through parietal scenes and statues. In this iconography, the pharaoh is invariably represented as the equal of the gods. In the religious speech, he is however only their humble servant, a zealous servant who makes multiple offerings. This piety expresses the hope of a just return of service. Filled with goods, the gods must favorably activate the forces of nature for a common benefit to all Egyptians. The only human being admitted to dialogue with the gods on an equal level, the Pharaoh was the supreme officiant; the first of the priests of the country. More widely, the pharaonic gesture covered all the fields of activity of the collective and ignored the separation of powers. Also, every member of the administration acts only in the name of the royal person, by delegation of power.

From the Pyramid Texts, the political actions of the sovereign were framed by a single maxim: "Bring Maat and repel Isfet", that is to say, promote harmony and repel chaos. As the nurturing father of the people, the Pharaoh ensured prosperity by calling upon the gods to regulate the waters of the Nile, by opening the granaries in case of famine and by guaranteeing a good distribution of arable land. Chief of the armies, the pharaoh was the brave protector of the borders. Like Ra who fights the serpent Apophis, the king of Egypt repels the plunderers of the desert, fights the invading armies and defeats the internal rebels. The Pharaoh was always the sole victor; standing up and knocking out a bunch of prisoners or shooting arrows from his battle chariot. As the only legislator, the laws and decrees he promulgated were seen as inspired by divine wisdom. This legislation, kept in the archives and placed under the responsibility of the vizier, applied to all, for the common good and social agreement.

Regalia

Scepters and staves

Sceptres and staves were a general symbol of authority in ancient Egypt.[25] One of the earliest royal scepters was discovered in the tomb of Khasekhemwy in Abydos.[25] Kings were also known to carry a staff, and Anedjib is shown on stone vessels carrying a so-called mks-staff.[26] The scepter with the longest history seems to be the heqa-sceptre, sometimes described as the shepherd's crook.[27] The earliest examples of this piece of regalia dates to prehistoric Egypt. A scepter was found in a tomb at Abydos that dates to Naqada III.

Another scepter associated with the king is the was-sceptre.[27] This is a long staff mounted with an animal head. The earliest known depictions of the was-scepter date to the First Dynasty. The was-scepter is shown in the hands of both kings and deities.

The flail later was closely related to the heqa-scepter (the crook and flail), but in early representations the king was also depicted solely with the flail, as shown in a late pre-dynastic knife handle that is now in the Metropolitan museum, and on the Narmer Macehead.[28]

The Uraeus

The earliest evidence known of the Uraeus—a rearing cobra—is from the reign of Den from the first dynasty. The cobra supposedly protected the king by spitting fire at its enemies.[29]

Crowns and headdresses

Deshret

The red crown of Lower Egypt, the Deshret crown, dates back to pre-dynastic times and symbolised chief ruler. A red crown has been found on a pottery shard from Naqada, and later, Narmer is shown wearing the red crown on both the Narmer Macehead and the Narmer Palette.

Hedjet

The white crown of Upper Egypt, the Hedjet, was worn in the Predynastic Period by Scorpion II, and, later, by Narmer.

Pschent

This is the combination of the Deshret and Hedjet crowns into a double crown, called the Pschent crown. It is first documented in the middle of the First Dynasty of Egypt. The earliest depiction may date to the reign of Djet, and is otherwise surely attested during the reign of Den.[31]

Khat

The khat headdress consists of a kind of "kerchief" whose end is tied similarly to a ponytail. The earliest depictions of the khat headdress comes from the reign of Den, but is not found again until the reign of Djoser.

Nemes

The Nemes headdress dates from the time of Djoser. It is the most common type of royal headgear depicted throughout Pharaonic Egypt. Any other type of crown, apart from the Khat headdress, has been commonly depicted on top of the Nemes. The statue from his Serdab in Saqqara shows the king wearing the nemes headdress.[31]

Atef

Osiris is shown to wear the Atef crown, which is an elaborate Hedjet with feathers and disks. Depictions of kings wearing the Atef crown originate from the Old Kingdom.

Hemhem

The Hemhem crown is usually depicted on top of Nemes, Pschent, or Deshret crowns. It is an ornate, triple Atef with corkscrew sheep horns and usually two uraei. The depiction of this crown begins among New Kingdom rulers during the Early Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt.

Khepresh

Also called the blue crown, the Khepresh crown has been depicted in art since the New Kingdom. It is often depicted being worn in battle, but it was also frequently worn during ceremonies. It used to be called a war crown by many, but modern historians refrain from defining it thus.

Physical evidence

Egyptologist Bob Brier has noted that despite their widespread depiction in royal portraits, no ancient Egyptian crown has ever been discovered. The tomb of Tutankhamun that was discovered largely intact, contained such royal regalia as a crook and flail, but no crown was found among his funerary equipment. Diadems have been discovered.[32] It is presumed that crowns would have been believed to have magical properties and were used in rituals. Brier's speculation is that crowns were religious or state items, so a dead king likely could not retain a crown as a personal possession. The crowns may have been passed along to the successor, much as the crowns of modern monarchies.[33]

Titles

During the Early Dynastic Period kings had three titles. The Horus name is the oldest and dates to the late pre-dynastic period. The Nesu Bity name was added during the First Dynasty. The Nebty name (Two Ladies) was first introduced toward the end of the First Dynasty.[31] The Golden falcon (bik-nbw) name is not well understood. The prenomen and nomen were introduced later and are traditionally enclosed in a cartouche.[34] By the Middle Kingdom, the official titulary of the ruler consisted of five names; Horus, Nebty, Golden Horus, nomen, and prenomen [35] for some rulers, only one or two of them may be known.

Horus name

The Horus name was adopted by the king, when taking the throne. The name was written within a square frame representing the palace, named a serekh. The earliest known example of a serekh dates to the reign of king Ka, before the First Dynasty.[36] The Horus name of several early kings expresses a relationship with Horus. Aha refers to "Horus the fighter", Djer refers to "Horus the strong", etc. Later kings express ideals of kingship in their Horus names. Khasekhemwy refers to "Horus: the two powers are at peace", while Nebra refers to "Horus, Lord of the Sun".[31]

Nesu Bity name

The Nesu Bity name, also known as prenomen, was one of the new developments from the reign of Den. The name would follow the glyphs for the "Sedge and the Bee". The title is usually translated as king of Upper and Lower Egypt. The nsw bity name may have been the birth name of the king. It was often the name by which kings were recorded in the later annals and king lists.[31]

Nebty name

The earliest example of a Nebty (Two Ladies) name comes from the reign of king Aha from the First Dynasty. The title links the king with the goddesses of Upper and Lower Egypt, Nekhbet and Wadjet.[31][34] The title is preceded by the vulture (Nekhbet) and the cobra (Wadjet) standing on a basket (the neb sign).[31]

Golden Horus

The Golden Horus or Golden Falcon name was preceded by a falcon on a gold or nbw sign. The title may have represented the divine status of the king. The Horus associated with gold may be referring to the idea that the bodies of the deities were made of gold and the pyramids and obelisks are representations of (golden) sun-rays. The gold sign may also be a reference to Nubt, the city of Set. This would suggest that the iconography represents Horus conquering Set.[31]

Nomen and prenomen

The prenomen and nomen were contained in a cartouche. The prenomen often followed the King of Upper and Lower Egypt (nsw bity) or Lord of the Two Lands (nebtawy) title. The prenomen often incorporated the name of Re. The nomen often followed the title, Son of Re (sa-ra), or the title, Lord of Appearances (neb-kha).[34]

Divinity

Ancient Egypt

In Ancient Egypt, the Pharaoh was often considered to be divine. This precept originated before 3000 BCE and the Egyptian office of divine kingship would go on to influence many other societies and kingdoms, surviving into the modern era. The Pharaoh also became a mediator between the gods and man. This institution represents an innovation over that of Sumerian city-states where, though the clan leader or king mediated between his people and the gods, did not himself represent a god on Earth. The few Sumerian exceptions to this would post-date the origins of this practice in ancient Egypt. For example, the legendary king Gilgamesh, thought to have reigned in Uruk as a contemporary of the Egyptian ruler Djoser, was cast as having had his mother as the Mesopotamian goddess Ninsun alongside his father, the previous human ruler of Uruk. Another Mesopotamian example of a god-king was Naram-Sin of Akkad. During the Early Dynastic Period, the Pharaoh was represented as the divine incarnation of Horus, and the unifier of Upper and Lower Egypt. By the time of Djedefre (26th century BCE), the Pharaoh also ceased to have a father, as his mother was magically impregnated by the solar deity Ra. According to Pyramid Text Utterance 571, "... the King was fashioned by his father Atum before the sky existed, before earth existed, before men existed, before the gods were born, before death existed ..." According to an inscription on the statue of Horemheb (14th–13th centuries BCE): "he [Horemheb] already came out of his mother's bosom adorned with the prestige and the divine color ..."[37] Inscriptions regularly described the Pharaoh as the "good god" or "perfect god" (nfr ntr). By the time of the New Kingdom, the divinity of the king was imbued as he possessed the manifestation of the god Amun-Re; this was referred to as his 'living royal ka' which he received during the coronation ceremony. The divinity of Pharaoh was still held to during the period of Persian domination of Egypt. The Persian emperor Darius the Great (522–486 BCE) was referred to as a divine being in Egyptian temple texts. Such descriptions continued and were designated to Alexander the Great after his conquest of Egypt, and later still for the rulers of the Ptolemaic Kingdom that succeeded Alexander's rule.[38]

Classical Greece

Descriptions of the divinity of the Pharaoh are much more infrequent in sources from Classical Greece. One Ptolemaic-era hymn describes the divinity of the Pharaoh, though this may reflect Greek notions of divine kingship just as much as it could reflect Egyptian ones. The historian Herodotus explicitly denies this, claiming that Egyptian priests rejected any notion of the divinity of the king. The only explicit classical Greek source which describes the divinity of Pharaoh is contained in the writings of Diodorus Siculus in the 1st century BCE, who in turn relies on Hecataeus of Abdera as his source of information. Diodorus slightly contradicts himself in a different passage where he asserts that Darius I was the first ruler of Egypt to be honored as a king.[38]

Rabbinic literature

Even after the reign of the Egyptian kings and pharaohs, the notion of Pharaoh's self-notion as a divine being survived and is described in rabbinic literature. In these sources, the Pharaoh is described as hubristically asserting his own divinity and yet, compared to the one true God, is no more than an impotent human. Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael, Shirah 8:32 names Pharaoh among those who proclaimed themselves as gods, alongside Sennacherib and Nebuchadnezzar.[39] Genesis Rabbah 89:3 invokes Pharaoh describing himself as the god over the Nile river. In Exodus Rabbah 10:2, Pharaoh boasts that he is the creator and owner of the Nile. God is then said to have responded to this statement by challenging the Pharaoh over who owns the Nile, as God proceeds to create a disaster by bringing forth frogs from it that consume Egypt's agriculture. In other midrashic texts, Pharaoh asserts himself as the creator of the universe and even of himself.[40] In the Tanhuma, in commentary on Ezekiel 29:9, Pharaoh is said to have proclaimed himself as lord of the universe. Pharaoh is represented as a heretical figure who presents himself as divine, and these texts then claim that his claims were exposed when he had to go to the Nile to relieve himself.[41]

See also

Notes

- ^ Likely pronounced parūwʿar in Old Egyptian (c. 2500 BCE) and Middle Egyptian (c. 1700 BCE), and pərəʾaʿ or pərəʾōʿ in Late Egyptian (c. 800 BCE)

- ^ nb.f means "his lord", the monarchs were introduced with (.f) for his, (.k) for your.[19]

References

- ^ a b Clayton 1995, p. 217. "Although paying lip-service to the old ideas and religion, in varying degrees, pharaonic Egypt had in effect died with the last native pharaoh, Nectanebo II in 343 BCE."

- ^ Tyldesley, Joyce (2009). Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt. Profile Books. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-1861979018.

The Ptolemies believed themselves to be a valid Egyptian dynasty, and devoted a great deal of time and money to demonstrating that they were the theological continuation of all the dynasties that had gone before. Cleopatra defined herself as an Egyptian queen, and drew on the iconography and cultural references of earlier queens to reinforce her position. Her people and her contemporaries accepted her as such.

- ^ von Beckerath, Jürgen (1999). Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen. Verlag Philipp von Zabern. pp. 266–267. ISBN 978-3422008328.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 978-1405881180

- ^ "Strong's Hebrew Concordance – 6547. Paroh". Bible Hub. Archived from the original on 2022-10-18. Retrieved 2022-10-20.

- ^ Clayton, Peter A. Chronicle of the Pharaohs the Reign-by-reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson, CE 2012. Print.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (2002). Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-66420-7.

- ^ Bierbrier, Morris L. (2008). Historical Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6250-0.

- ^ "Pharaoh". AncientEgypt.co.uk. The British Museum. 1999. Archived from the original on 27 November 1999. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ Mark, Joshua (2 September 2009). "Pharaoh – World History Encyclopedia". World History Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ Hagen, Rose-Marie; Hagen, Rainer (2007). Egypt Art. New Holland Publishers Pty, Ltd. ISBN 978-3-8228-5458-7.

- ^ "The royal crowns of Egypt". Egypt Exploration Society. 7 March 2019. Archived from the original on 2022-05-18. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- ^ Gaskell, G. (2016). A Dictionary of the Sacred Language of All Scriptures and Myths. Routledge Revivals. ISBN 978-1-317-58942-6.

- ^ A. Gardiner, Ancient Egyptian Grammar (3rd ed., 1957), 71–76.

- ^ Hieratic Papyrus from Kahun and Gurob, F. LL. Griffith, 38, 17.

- ^ Petrie, W. M. (William Matthew Flinders); Sayce, A. H. (Archibald Henry); Griffith, F. Ll (Francis Llewellyn) (1891). Illahun, Kahun and Gurob : 1889–1890. Cornell University Library. London : D. Nutt. pp. 50.

- ^ Robert Mond and O.H. Meyers. Temples of Armant, a Preliminary Survey: The Text, The Egypt Exploration Society, London, 1940, 160.

- ^ "pharaoh" in Encyclopædia Britannica. Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008.

- ^ a b c Doxey, Denise M. (1998). Egyptian Non-Royal Epithets in the Middle Kingdom: A Social and Historical Analysis. Brill. p. 119. ISBN 90-04-11077-1.

- ^ J-M. Kruchten, Les annales des pretres de Karnak (OLA 32), 1989, pp. 474–478.

- ^ Alan Gardiner, "The Dakhleh Stela", Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 19, No. 1/2 (May, 1933) pp. 193–200.

- ^ Herodotus, Histories 2.111.1. See Anne Burton (1972). Diodorus Siculus, Book 1: A Commentary. Brill., commenting on ch. 59.1.

- ^ Elazar Ari Lipinski: "Pesach – A holiday of questions. About the Haggadah-Commentary Zevach Pesach of Rabbi Isaak Abarbanel (1437–1508). Archived 2017-03-16 at the Wayback Machine Explaining the meaning of the name Pharaoh." Published first in German in the official quarterly of the Organization of the Jewish Communities of Bavaria: Jüdisches Leben in Bayern. Mitteilungsblatt des Landesverbandes der Israelitischen Kultusgemeinden in Bayern. Pessach-Ausgabe Nr. 109, 2009, ZDB-ID 2077457-6, S. 3–4.

- ^ Walter C. Till: "Koptische Grammatik". VEB Verlag Enzyklopädie, Leipzig, 1961. p. 62.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 158.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 159.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 160.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 161.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 162.

- ^ "Guardian Figure". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 18 January 2022. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001 ISBN 978-0-415-26011-4

- ^ Shaw, Garry J. The Pharaoh, Life at Court and on Campaign. Thames and Hudson, 2012, pp. 21, 77.

- ^ Bob Brier, The Murder of Tutankhamen, 1998, p. 95.

- ^ a b c Dodson, Aidan and Hilton, Dyan. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2004. ISBN 0-500-05128-3

- ^ Ian Shaw, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press 2000, p. 477

- ^ Toby A. H. Wilkinson, Early Dynastic Egypt, Routledge 1999, pp. 57f.

- ^ Najovits, Simson R. (2003). Egypt, trunk of the tree. 1: The contexts. Algora Publ. pp. 151–157. ISBN 9780875862347.

- ^ a b Collins, Andrew (2014). "The Divinity of the Pharaoh in Greek Sources". The Classical Quarterly. 64 (2): 841–844, also see n. 1. doi:10.1017/S000983881400007X. ISSN 0009-8388.

- ^ Patmore, Hector M. (2008). Adam, Satan, and the King of Tyre: The Reception of Ezekiel 28:11-19 in Judaism and Christianity in Late Antiquity (PDF) (PhD thesis). Durham University. p. 170. Retrieved 2024-12-18.

- ^ Ulmer, Rivka (2009). Egyptian Cultural Icons in Midrash. Studia Judaica. Berlin: Walter De Gruyter. pp. 74–76. ISBN 978-3-11-022392-7.

- ^ Ulmer, Rivka (2016). "Egyptian Motifs in Late Antique Mosaics and Rabbinic Texts". In Kalimi, Isaac (ed.). Bridging Between Sister Religions: Studies of Jewish and Christian Scriptures Offered in Honor of Prof. John T. Townsend. The Brill Reference Library of Judaism. Leiden: Brill. p. 208. ISBN 978-90-04-32454-1.

Bibliography

- Shaw, Garry J. The Pharaoh, Life at Court and on Campaign, Thames and Hudson, 2012.

- Sir Alan Gardiner Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs, Third Edition, Revised. London: Oxford University Press, 1964. Excursus A, pp. 71–76.

- Jan Assmann, "Der Mythos des Gottkönigs im Alten Ägypten", in Christine Schmitz und Anja Bettenworth (hg.), Menschen – Heros – Gott: Weltentwürfe und Lebensmodelle im Mythos der Vormoderne (Stuttgart, Franz Steiner Verlag, 2009), pp. 11–26.