Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick | |

|---|---|

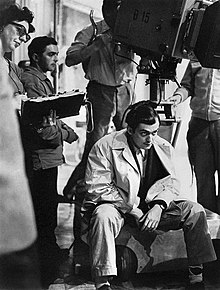

Kubrick c. 1973–74 | |

| Born | July 26, 1928 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | March 7, 1999 (aged 70) Childwickbury, Hertfordshire, England |

| Occupations |

|

| Works | Full list |

| Spouses | Toba Metz

(m. 1948; div. 1951) |

| Children | 2, including Vivian |

| Signature | |

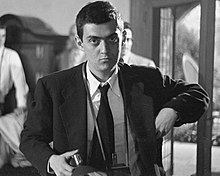

Stanley Kubrick (/ˈkuːbrɪk/; July 26, 1928 – March 7, 1999) was an American film director, screenwriter, producer, and photographer. Widely considered one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, his films were nearly all adaptations of novels or short stories, spanning a number of genres and gaining recognition for their intense attention to detail, innovative cinematography, extensive set design, and dark humor.

Born and raised in New York City, Kubrick was an average school student but displayed a keen interest in literature, photography, and film from a young age; he began to teach himself all aspects of film producing and directing after graduating from high school. After working as a photographer for Look magazine in the late 1940s and early 1950s, he began making low-budget short films and made his first major Hollywood film, The Killing, for United Artists in 1956. This was followed by two collaborations with Kirk Douglas: the anti-war film Paths of Glory (1957) and the historical epic film Spartacus (1960).

In 1961, Kubrick left the United States due to concerns about crime in the country, as well as a growing dislike for how Hollywood operated and creative differences with Douglas and the film studios. He settled in England, which he would leave only a handful of times for the rest of his life. In 1978, he made his home at Childwickbury Manor, which he shared with his wife Christiane, and which became his workplace where he centralized the writing, research, editing, and management of his productions. This permitted him almost complete artistic control over his films, with the rare advantage of financial support from major Hollywood studios. His first productions in England were two films with Peter Sellers: an adaptation of Lolita (1962) and the Cold War black comedy Dr. Strangelove (1964).

A perfectionist who assumed direct control over most aspects of his filmmaking, Kubrick cultivated an expertise in writing, editing, color grading, promotion, and exhibition. He was famous for the painstaking care taken in researching his films and staging scenes, performed in close coordination with his actors, crew, and other collaborators. He frequently asked for several dozen retakes of the same shot in a film, often confusing and frustrating his actors. Despite the notoriety this provoked, many of Kubrick's films broke new cinematic ground and are now considered landmarks. The scientific realism and innovative special effects in his science fiction epic 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) were a first in cinema history, and the film earned him his only Academy Award (for Best Visual Effects). Filmmaker Steven Spielberg has referred to 2001 as his generation's "big bang" and it is regarded as one of the greatest films ever made.

While many of Kubrick's films were controversial and initially received mixed reviews upon release—particularly the brutal A Clockwork Orange (1971), which Kubrick withdrew from circulation in the UK following a media frenzy—most were nominated for Academy Awards, Golden Globes, or BAFTA Awards, and underwent critical re-evaluations. For the 18th-century period film Barry Lyndon (1975), Kubrick obtained lenses developed by Carl Zeiss for NASA to film scenes by candlelight. With the horror film The Shining (1980), he became one of the first directors to make use of a Steadicam for stabilized and fluid tracking shots, a technology vital to his Vietnam War film Full Metal Jacket (1987). A few days after hosting a screening for his family and the stars of his final film, the erotic drama Eyes Wide Shut (1999), he died from a heart attack at the age of 70.

Early life

Kubrick was born to a Jewish family in the Lying-In Hospital in New York City's Manhattan borough on July 26, 1928.[1][2] He was the first of two children of Jacob Leonard Kubrick (May 21, 1902 – October 19, 1985), known as Jack or Jacques, and his wife Sadie Gertrude Kubrick (née Perveler; October 28, 1903 – April 23, 1985), known as Gert. His sister Barbara Mary Kubrick was born in May 1934.[3] Jack, whose parents and paternal grandparents were of Polish-Jewish and Romanian-Jewish origin,[1] was a homeopathic doctor,[4] graduating from the New York Homeopathic Medical College in 1927, the same year he married Kubrick's mother, who was the child of Austrian-Jewish immigrants.[5] On December 27, 1899, Kubrick's great-grandfather Hersh Kubrick arrived at Ellis Island via Liverpool by ship at the age of 47, leaving behind his wife and two grown children (one of whom was Stanley's grandfather Elias) to start a new life with a younger woman.[6] Elias followed in 1902.[7] At Stanley's birth, the Kubricks lived in the Bronx.[8] His parents married in a Jewish ceremony, but Kubrick was not raised religious and later professed an atheistic view of the universe.[9] His father was a physician and, by the standards of the West Bronx, the family was fairly wealthy.[10]

Soon after his sister's birth, Kubrick began schooling in Public School 3 in the Bronx and moved to Public School 90 in June 1938. His IQ was discovered to be above average but his attendance was poor.[2] He displayed an interest in literature from a young age and began reading Greek and Roman myths and the fables of the Brothers Grimm, which "instilled in him a lifelong affinity with Europe".[11] He spent most Saturdays during the summer watching the New York Yankees and later photographed two boys watching the game in an assignment for Look magazine to emulate his own childhood excitement with baseball.[10] When Kubrick was 12, his father Jack taught him chess. The game remained a lifelong interest of Kubrick's,[12] appearing in many of his films.[13] Kubrick, who later became a member of the United States Chess Federation, explained that chess helped him develop "patience and discipline" in making decisions.[14] When Kubrick was 13, his father bought him a Graflex camera, triggering a fascination with still photography. He befriended a neighbor, Marvin Traub, who shared his passion for photography.[15] Traub had his own darkroom where he and the young Kubrick would spend many hours perusing photographs and watching the chemicals "magically make images on photographic paper".[3] The two indulged in numerous photographic projects for which they roamed the streets looking for interesting subjects to capture and spent time in local cinemas studying films. Freelance photographer Weegee (Arthur Fellig) had a considerable influence on Kubrick's development as a photographer; Kubrick later hired Fellig as the special stills photographer for Dr. Strangelove (1964).[16] As a teenager, Kubrick was also interested in jazz and briefly attempted a career as a drummer.[17]

Kubrick attended William Howard Taft High School from 1941 to 1945.[18] He joined the school's photography club, which permitted him to photograph the school's events in their magazine.[3] He was a mediocre student, with a 67/D+ grade average.[19] Introverted and shy, Kubrick had a low attendance record and often skipped school to watch double-feature films.[20] He graduated in 1945 but his poor grades, combined with the demand for college admissions from soldiers returning from World War II, eliminated any hope of higher education. Later in life Kubrick spoke disdainfully of his education and of American schooling as a whole, maintaining that schools were ineffective in stimulating critical thinking and student interest. His father was disappointed in his son's failure to achieve the excellence in school of which he knew Stanley was fully capable. Jack also encouraged Stanley to read from the family library at home, while permitting Stanley to take up photography as a serious hobby.[21]

Photographic career

While in high school, Kubrick was chosen as an official school photographer. In the mid-1940s, since he was unable to gain admission to day session classes at colleges, he briefly attended evening classes at the City College of New York,[22] which had open admissions. Eventually, he sold a photographic series to Look magazine,[23][a] which was printed on June 26, 1945. Kubrick supplemented his income by playing chess "for quarters" in Washington Square Park and various Manhattan chess clubs.[25]

In 1946, he became an apprentice photographer for Look and later a full-time staff photographer. G. Warren Schloat Jr., another new photographer for the magazine at the time, recalled that he thought Kubrick lacked the personality to make it as a director in Hollywood, remarking, "Stanley was a quiet fellow. He didn't say much. He was thin, skinny, and kind of poor—like we all were."[26] Kubrick quickly became known for his story-telling in photographs. His first, published on April 16, 1946, was titled "A Short Story from a Movie Balcony" and staged a fracas between a man and a woman, during which the man is slapped in the face, caught genuinely by surprise.[23] In another assignment, Kubrick took 18 pictures of various people waiting in a dental office. It has been said retrospectively that this project demonstrated an early interest of Kubrick in capturing individuals and their feelings in mundane environments.[27] In 1948, he was sent to Portugal to document a travel piece, and later that year covered the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus in Sarasota, Florida.[28][b]

A boxing enthusiast, Kubrick eventually began photographing boxing matches for the magazine. His earliest, "Prizefighter", was published on January 18, 1949, and captured a boxing match and the events leading up to it, featuring American middleweight Walter Cartier.[30] On April 2, 1949, he published photo essay "Chicago-City of Extremes" in Look, which displayed his talent early on for creating atmosphere with imagery. The following year, in July 1950, the magazine published his photo essay, "Working Debutante – Betsy von Furstenberg", which featured a Pablo Picasso portrait of Angel F. de Soto in the background.[31] Kubrick was also assigned to photograph numerous jazz musicians, from Frank Sinatra and Erroll Garner to George Lewis, Eddie Condon, Phil Napoleon, Papa Celestin, Alphonse Picou, Muggsy Spanier, Sharkey Bonano, and others.[32]

Kubrick married his high-school sweetheart Toba Metz on May 28, 1948. They lived together in a small apartment at 36 West 16th Street, off Sixth Avenue just north of Greenwich Village.[33] During this time, Kubrick began frequenting film screenings at the Museum of Modern Art and New York City cinemas. He was inspired by the complex, fluid camerawork of French director Max Ophüls, whose films influenced Kubrick's visual style, and by director Elia Kazan, whom he described as America's "best director" at that time, with his ability of "performing miracles" with his actors.[34] Friends began to notice Kubrick had become obsessed with the art of filmmaking—one friend, David Vaughan, observed that Kubrick would scrutinize the film at the cinema when it went silent, and would go back to reading his paper when people started talking.[23] He spent many hours reading books on film theory and writing notes. He was particularly inspired by Sergei Eisenstein and Arthur Rothstein, the photographic technical director of Look magazine.[35][c]

Film career

Short films (1951–1953)

Kubrick shared a love of film with his school friend Alexander Singer, who after graduating from high school had the intention of directing a film version of Homer's Iliad. Through Singer, who worked in the offices of the newsreel production company, The March of Time, Kubrick learned it could cost $40,000 to make a proper short film, money he could not afford. He had $1500 in savings and produced a few short documentaries fueled by encouragement from Singer. He began learning all he could about filmmaking on his own, calling film suppliers, laboratories, and equipment rental houses.[36]

Kubrick decided to make a short film documentary about boxer Walter Cartier, whom he had photographed and written about for Look magazine a year earlier. He rented a camera and produced a 16-minute black-and-white documentary, Day of the Fight. Kubrick found the money independently to finance it. He had considered asking Montgomery Clift to narrate it, whom he had met during a photographic session for Look, but settled on CBS news veteran Douglas Edwards.[37] According to Paul Duncan the film was "remarkably accomplished for a first film", and used a backward tracking shot to film a scene in which Cartier and his brother walk towards the camera, a device which later became one of Kubrick's characteristic camera movements.[38] Vincent Cartier, Walter's brother and manager, later reflected on his observations of Kubrick during the filming. He said, "Stanley was a very stoic, impassive but imaginative type person with strong, imaginative thoughts. He commanded respect in a quiet, shy way. Whatever he wanted, you complied, he just captivated you. Anybody who worked with Stanley did just what Stanley wanted".[36][d] After a score was added by Singer's friend Gerald Fried, Kubrick had spent $3900 in making it, and sold it to RKO-Pathé for $4000, which was the most the company had ever paid for a short film at the time.[38] Kubrick described his first effort at filmmaking as having been valuable since he believed himself to have been forced to do most of the work,[39] and he later declared that the "best education in film is to make one".[3]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Inspired by this early success, Kubrick quit his job at Look and visited professional filmmakers in New York City, asking many detailed questions about the technical aspects of filmmaking. He stated that he was given the confidence during this period to become a filmmaker because of the number of bad films he had seen, remarking, "I don't know a goddamn thing about movies, but I know I can make a better film than that".[40] He began making Flying Padre (1951), a film which documents Reverend Fred Stadtmueller, who travels some 4,000 miles to visit his 11 churches. The film was originally going to be called "Sky Pilot", a pun on the slang term for a priest.[41] During the course of the film, the priest performs a burial service, confronts a boy bullying a girl, and makes an emergency flight to aid a sick mother and baby into an ambulance. Several of the views from and of the plane in Flying Padre are later echoed in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) with the footage of the spacecraft, and a series of close-ups on the faces of people attending the funeral were most likely inspired by Sergei Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin (1925) and Ivan the Terrible (1944/1958).[38]

Flying Padre was followed by The Seafarers (1953), Kubrick's first color film, which was shot for the Seafarers International Union in June 1953. It depicted the logistics of a democratic union and focused more on the amenities of seafaring other than the act. For the cafeteria scene in the film, Kubrick chose a dolly shot to establish the life of the seafarer's community; this kind of shot would later become a signature technique. The sequence of Paul Hall, secretary-treasurer of the SIU Atlantic and gulf district, speaking to members of the union echoes scenes from Eisenstein's Strike (1925) and October (1928).[42] Day of the Fight, Flying Padre and The Seafarers constitute Kubrick's only surviving documentary works; some historians believe he made others.[43]

Early feature work (1953–1955)

After raising $1000 showing his short films to friends and family, Kubrick found the finances to begin making his first feature film, Fear and Desire (1953), originally running with the title The Trap, written by his friend Howard Sackler. Kubrick's uncle, Martin Perveler, a Los Angeles pharmacy owner, invested a further $9000 on condition that he be credited as executive producer of the film.[44] Kubrick assembled several actors and a small crew totaling 14 people (five actors, five crewmen, and four others to help transport the equipment) and flew to the San Gabriel Mountains in California for a five-week, low-budget shoot.[44] Later renamed The Shape of Fear before finally being named Fear and Desire, it is a fictional allegory about a team of soldiers who survive a plane crash and are caught behind enemy lines in a war. During the course of the film, one of the soldiers becomes infatuated with an attractive girl in the woods and binds her to a tree. This scene is noted for its close-ups on the face of the actress. Kubrick had intended for Fear and Desire to be a silent picture in order to ensure low production costs; the added sounds, effects, and music ultimately brought production costs to around $53,000, exceeding the budget.[45] He was bailed out by producer Richard de Rochemont on the condition that he help in de Rochemont's production of a five-part television series about Abraham Lincoln on location in Hodgenville, Kentucky.[46]

Fear and Desire was a commercial failure, but garnered several positive reviews upon release. Critics such as the reviewer from The New York Times believed that Kubrick's professionalism as a photographer shone through in the picture, and that he "artistically caught glimpses of the grotesque attitudes of death, the wolfishness of hungry men, as well as their bestiality, and in one scene, the wracking effect of lust on a pitifully juvenile soldier and the pinioned girl he is guarding". Columbia University scholar Mark Van Doren was highly impressed by the scenes with the girl bound to the tree, remarking that it would live on as a "beautiful, terrifying and weird" sequence which illustrated Kubrick's immense talent and guaranteed his future success.[47] Kubrick himself later expressed embarrassment with Fear and Desire, and attempted over the years to keep prints of the film out of circulation.[48][e] During the production of the film, Kubrick almost killed his cast with poisonous gasses by mistake.[49]

Following Fear and Desire, Kubrick began working on ideas for a new boxing film. Due to the commercial failure of his first feature, Kubrick avoided asking for further investments, but commenced a film noir script with Howard O. Sackler. Originally under the title Kiss Me, Kill Me, and then The Nymph and the Maniac, Killer's Kiss (1955) is a 67-minute film noir about a young heavyweight boxer's involvement with a woman being abused by her criminal boss. Like Fear and Desire, it was privately funded by Kubrick's family and friends, with some $40,000 put forward from Bronx pharmacist Morris Bousse.[42] Kubrick began shooting footage in Times Square, and frequently explored during the filming process, experimenting with cinematography and considering the use of unconventional angles and imagery. He initially chose to record the sound on location, but encountered difficulties with shadows from the microphone booms, restricting camera movement. His decision to drop the sound in favor of imagery was a costly one; after 12–14 weeks shooting the picture, he spent some seven months and $35,000 working on the sound.[50] Alfred Hitchcock's Blackmail (1929) directly influenced the film with the painting laughing at a character, and Martin Scorsese has, in turn, cited Kubrick's innovative shooting angles and atmospheric shots in Killer's Kiss as an influence on Raging Bull (1980).[51] Actress Irene Kane, the star of Killer's Kiss, observed: "Stanley's a fascinating character. He thinks movies should move, with a minimum of dialogue, and he's all for sex and sadism".[52] Killer's Kiss met with limited commercial success and made very little money in comparison with its production budget of $75,000.[51] Critics have praised the film's camerawork, but its acting and story are generally considered mediocre.[53][f]

Hollywood success and beyond (1955–1962)

While playing chess in Washington Square, Kubrick met producer James B. Harris, who considered Kubrick "the most intelligent, most creative person I have ever come in contact with." The two formed the Harris-Kubrick Pictures Corporation in 1955.[56] Harris purchased the rights to Lionel White's novel Clean Break for $10,000[g] and Kubrick wrote the script,[58] but at Kubrick's suggestion, they hired film noir novelist Jim Thompson to write the dialog for the film—which became The Killing (1956)—about a meticulously planned racetrack robbery gone wrong. The film starred Sterling Hayden, who had impressed Kubrick with his performance in The Asphalt Jungle (1950).[59]

Kubrick and Harris moved to Los Angeles and signed with the Jaffe Agency to shoot the picture, which became Kubrick's first full-length feature film shot with a professional cast and crew. The Union in Hollywood stated that Kubrick would not be permitted to be both the director and the cinematographer, resulting in the hiring of veteran cinematographer Lucien Ballard. Kubrick agreed to waive his fee for the production, which was shot in 24 days on a budget of $330,000.[60] He clashed with Ballard during the shooting, and on one occasion Kubrick threatened to fire Ballard following a camera dispute, despite being aged only 27 and 20 years Ballard's junior.[59] Hayden recalled Kubrick was "cold and detached. Very mechanical, always confident. I've worked with few directors who are that good".[61]

The Killing failed to secure a proper release across the United States; the film made little money, and was promoted only at the last minute, as a second feature to the Western movie Bandido! (1956). Several contemporary critics lauded the film, with a reviewer for Time comparing its camerawork to that of Orson Welles.[62] Today, critics generally consider The Killing to be among the best films of Kubrick's early career; its nonlinear narrative and clinical execution also had a major influence on later directors of crime films, including Quentin Tarantino. Dore Schary of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) was highly impressed as well, and offered Kubrick and Harris $75,000 to write, direct, and produce a film, which ultimately became Paths of Glory (1957).[63][h]

Paths of Glory, set during World War I, is based on Humphrey Cobb's 1935 antiwar novel. Schary was familiar with the novel, but stated that MGM would not finance another war picture, given their backing of the anti-war film The Red Badge of Courage (1951).[i] After Schary was fired by MGM in a major shake-up, Kubrick and Harris managed to interest Kirk Douglas in playing Colonel Dax.[65][j] Douglas, in turn, signed Harris-Kubrick Pictures to a three-picture co-production deal with his film production company, Bryna Productions, which secured a financing and distribution deal for Paths of Glory and two subsequent films with United Artists.[66][67][68] The film, shot in Munich, from March 1957,[69] follows a French army unit ordered on an impossible mission, and follows with a war trial of three soldiers, arbitrarily chosen, for misconduct. Dax is assigned to defend the men at Court Martial. For the battle scene, Kubrick meticulously lined up six cameras one after the other along the boundary of no-man's land, with each camera capturing a specific field and numbered, and gave each of the hundreds of extras a number for the zone in which they would die.[70] Kubrick operated an Arriflex camera for the battle, zooming in on Douglas. Paths of Glory became Kubrick's first significant commercial success, and established him as an up-and-coming young filmmaker. Critics praised the film's unsentimental, spare, and unvarnished combat scenes and its raw, black-and-white cinematography.[71] Despite the praise, the Christmas release date was criticized,[72] and the subject was controversial in Europe. The film was banned in France until 1974 for its "unflattering" depiction of the French military, and was censored by the Swiss Army until 1970.[71]

In October 1957, after Paths of Glory had its world premiere in Germany, Bryna Productions optioned Canadian church minister-turned-master-safecracker Herbert Emerson Wilsons's autobiography, I Stole $16,000,000, especially for Stanley Kubrick and James B. Harris.[73][74] The picture was to be the second in the co-production deal between Bryna Productions and Harris-Kubrick Pictures, which Kubrick was to write and direct, Harris to co-produce and Douglas to co-produce and star.[73] In November 1957, Gavin Lambert was signed as story editor for I Stole $16,000,000, and with Kubrick, finished a script titled God Fearing Man, but the picture was never filmed.[75]

Marlon Brando contacted Kubrick, asking him to direct a film adaptation of the Charles Neider western novel, The Authentic Death of Hendry Jones, featuring Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid.[71][k] Brando was impressed, saying "Stanley is unusually perceptive, and delicately attuned to people. He has an adroit intellect, and is a creative thinker—not a repeater, not a fact-gatherer. He digests what he learns and brings to a new project an original point of view and a reserved passion".[77] The two worked on a script for six months, begun by a then unknown Sam Peckinpah. Many disputes broke out over the project, and in the end, Kubrick distanced himself from what would become One-Eyed Jacks (1961).[l]

In February 1959, Kubrick received a phone call from Kirk Douglas asking him to direct Spartacus (1960), based on the historical Spartacus and the Third Servile War. Douglas had acquired the rights to the novel by Howard Fast and blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo began penning the script.[82] It was produced by Douglas, who also starred as Spartacus, and cast Laurence Olivier as his foe, the Roman general and politician Marcus Licinius Crassus. Douglas hired Kubrick for a reported $150,000 fee to take over direction soon after he fired director Anthony Mann.[83] Kubrick had, at 31, already directed four feature films, and this became his largest by far, with a cast of over 10,000 and a budget of $6 million.[m] At the time, this was the most expensive film ever made in America, and Kubrick became the youngest director in Hollywood history to make an epic.[85] It was the first time that Kubrick filmed using the anamorphic 35 mm horizontal Super Technirama process to achieve ultra-high definition, which allowed him to capture large panoramic scenes, including one with 8,000 trained soldiers from Spain representing the Roman army.[n]

Disputes broke out during the filming of Spartacus. Kubrick complained about not having full creative control over the artistic aspects, insisting on improvising extensively during the production.[87][o] Kubrick and Douglas were also at odds over the script, with Kubrick angering Douglas when he cut all but two of his lines from the opening 30 minutes.[91] Despite the on-set troubles, Spartacus took $14.6 million at the box office in its first run.[87] The film established Kubrick as a major director, receiving six Academy Award nominations and winning four; it ultimately convinced him that if so much could be made of such a problematic production, he could achieve anything.[92] Spartacus also marked the end of the working relationship between Kubrick and Douglas.[p]

Collaboration with Peter Sellers (1962–1964)

Lolita

Kubrick and Harris decided to film Kubrick's next movie Lolita (1962) in England, due to clauses placed on the contract by producers Warner Bros. that gave them complete control over the film, and the fact that the Eady plan permitted producers to write off the costs if 80% of the crew were British. Instead, they signed a $1 million deal with Eliot Hyman's Associated Artists Productions, and a clause which gave them the artistic freedom that they desired.[95] Lolita, Kubrick's first attempt at black comedy, was an adaptation of the novel of the same name by Vladimir Nabokov, the story of a middle-aged college professor becoming infatuated with a 12-year-old girl. Stylistically, Lolita, starring Peter Sellers, James Mason, Shelley Winters, and Sue Lyon, was a transitional film for Kubrick, "marking the turning point from a naturalistic cinema ... to the surrealism of the later films", according to film critic Gene Youngblood.[96] Kubrick was impressed by the range of actor Peter Sellers and gave him one of his first opportunities to improvise wildly during shooting, while filming him with three cameras.[97][q]

Kubrick shot Lolita over 88 days on a $2 million budget at Elstree Studios, between October 1960 and March 1961.[100] Kubrick often clashed with Shelley Winters, whom he found "very difficult" and demanding, and nearly fired at one point.[101] Because of its provocative story, Lolita was Kubrick's first film to generate controversy; he was ultimately forced to comply with censors and remove much of the erotic element of the relationship between Mason's Humbert and Lyon's Lolita which had been evident in Nabokov's novel.[102] The film was not a major critical or commercial success, earning $3.7 million at the box office on its opening run.[103][r] Lolita has since become critically acclaimed.[104]

Dr. Strangelove

Kubrick's next project was Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), another satirical black comedy. Kubrick became preoccupied with the issue of nuclear war as the Cold War unfolded in the 1950s, and even considered moving to Australia because he feared that New York City might be a likely target for the Russians. He studied over 40 military and political research books on the subject and eventually reached the conclusion that "nobody really knew anything and the whole situation was absurd".[105]

After buying the rights to the novel Red Alert, Kubrick collaborated with its author, Peter George, on the script. It was originally written as a serious political thriller, but Kubrick decided that a "serious treatment" of the subject would not be believable, and thought that some of its most salient points would be fodder for comedy.[106] Kubrick's longtime producer and friend, James B. Harris, thought the film should be serious, and the two parted ways, amicably, over this disagreement—Harris going on to produce and direct the serious cold-war thriller The Bedford Incident.[107][108][109] Kubrick and Red Alert author George then reworked the script as a satire (provisionally titled "The Delicate Balance of Terror") in which the plot of Red Alert was situated as a film-within-a-film made by an alien intelligence, but this idea was also abandoned, and Kubrick decided to make the film as "an outrageous black comedy".[110]

Just before filming began, Kubrick hired noted journalist and satirical author Terry Southern to transform the script into its final form, a black comedy, loaded with sexual innuendo,[111] becoming a film which showed Kubrick's talents as a "unique kind of absurdist" according to the film scholar Abrams.[112] Southern made major contributions to the final script, and was co-credited (above Peter George) in the film's opening titles; his perceived role in the writing later led to a public rift between Kubrick and Peter George, who subsequently complained in a letter to Life magazine that Southern's intense but relatively brief (November 16 to December 28, 1962) involvement with the project was being given undue prominence in the media, while his own role as the author of the film's source novel, and his ten-month stint as the script's co-writer, were being downplayed – a perception Kubrick evidently did little to address.[113]

Kubrick found that Dr. Strangelove, a $2 million production which employed what became the "first important visual effects crew in the world",[114] would be impossible to make in the U.S. for various technical and political reasons, forcing him to move production to England. It was shot in 15 weeks, ending in April 1963, after which Kubrick spent eight months editing it.[115] Peter Sellers again agreed to work with Kubrick, and ended up playing three different roles in the film.[s]

Upon release, the film stirred up much controversy and mixed opinions. The New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther worried that it was a "discredit and even contempt for our whole defense establishment ... the most shattering sick joke I've ever come across",[117] while Robert Brustein of Out of This World in a February 1970 article called it a "juvenalian satire".[115] Kubrick responded to the criticism, stating: "A satirist is someone who has a very skeptical view of human nature, but who still has the optimism to make some sort of a joke out of it. However brutal that joke might be".[118] Today, the film is considered to be one of the sharpest comedy films ever made, and holds a near-perfect 98% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 91 reviews as of November 2020[update].[119] It was named the 39th-greatest American film and third-greatest American comedy film of all time by the American Film Institute,[120][121] and in 2010, it was named the sixth-best comedy film of all time by The Guardian.[122]

Science fiction (1965–1971)

2001: A Space Odyssey

Kubrick spent five years developing his next film, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), having been highly impressed with science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke's novel Childhood's End, about a superior alien race who assist mankind in eliminating their old selves. After meeting Clarke in New York City in April 1964, Kubrick made the suggestion to work on his 1948 short story "The Sentinel", in which a monolith found on the Moon alerts aliens of mankind.[123] That year, Clarke began writing the novel 2001: A Space Odyssey and collaborated with Kubrick on a screenplay. The film's theme, the birthing of one intelligence by another, is developed in two parallel intersecting stories on two different time scales. One depicts evolutionary transitions between various stages of man, from ape to "star child", as man is reborn into a new existence, each step shepherded by an enigmatic alien intelligence seen only in its artifacts: a series of seemingly indestructible eons-old black monoliths. In space, the enemy is a supercomputer known as HAL who runs the spaceship, a character which novelist Clancy Sigal described as being "far, far more human, more humorous and conceivably decent than anything else that may emerge from this far-seeing enterprise".[124][t]

Kubrick intensively researched for the film, paying particular attention to accuracy and detail in what the future might look like. He was granted permission by NASA to observe the spacecraft being used in the Ranger 9 mission for accuracy.[126] Filming commenced on December 29, 1965, with the excavation of the monolith on the moon,[127] and footage was shot in Namib Desert in early 1967, with the ape scenes completed later that year. The special effects team continued working until the end of the year to complete the film, taking the cost to $10.5 million.[127] 2001: A Space Odyssey was conceived as a Cinerama spectacle and was photographed in Super Panavision 70, giving the viewer a "dazzling mix of imagination and science" through ground-breaking effects, which earned Kubrick his only personal Oscar, an Academy Award for Visual Effects.[127][u] Kubrick said of the concept of the film in an interview with Rolling Stone: "On the deepest psychological level, the film's plot symbolized the search for God, and finally postulates what is little less than a scientific definition of God. The film revolves around this metaphysical conception, and the realistic hardware and the documentary feelings about everything were necessary in order to undermine your built-in resistance to the poetical concept".[129]

Upon release in 1968, 2001: A Space Odyssey was not an immediate hit among critics, who faulted its lack of dialog, slow pacing, and seemingly impenetrable storyline.[130] The film appeared to defy genre convention, much unlike any science-fiction movie before it,[131] and clearly different from any of Kubrick's earlier works. Kubrick was particularly outraged by a scathing review from Pauline Kael, who called it "the biggest amateur movie of them all", with Kubrick doing "really every dumb thing he ever wanted to do".[132] Despite mixed contemporary critical reviews, 2001 gradually gained popularity and earned $31 million worldwide by the end of 1972.[127][v] Today, it is widely considered to be one of the greatest and most influential films ever made and is a staple on All Time Top 10 lists.[134][135] Baxter describes the film as "one of the most admired and discussed creations in the history of cinema",[136] and Steven Spielberg has referred to it as "the big bang of his film making generation".[137] For biographer Vincent LoBrutto it "positioned Stanley Kubrick as a pure artist ranked among the masters of cinema".[138] The film marked Kubrick's first use of classical music. Roger Ebert writes: "Although Kubrick originally commissioned an original score from Alex North, he used classical recordings as a temporary track while editing the film, and they worked so well that he kept them. This was a crucial decision. North's score, which is available on a recording, is a good job of film composition, but would have been wrong for 2001 because, like all scores, it attempts to underline the action -- to give us emotional cues. The classical music chosen by Kubrick exists outside the action. It uplifts. It wants to be sublime; it brings a seriousness and transcendence to the visuals", citing Kubrick's use of Johann Strauss II's "The Blue Danube" and Richard Strauss's Also sprach Zarathustra.[139]

A Clockwork Orange

After completing 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick searched for a project that he could film quickly on a more modest budget. He settled on A Clockwork Orange (1971) at the end of 1969, an exploration of violence and experimental rehabilitation by law enforcement authorities, based around the character of Alex (portrayed by Malcolm McDowell). Kubrick had received a copy of Anthony Burgess's novel of the same name from Terry Southern while they were working on Dr. Strangelove, but had rejected it on the grounds that Nadsat,[w] a street language for young teenagers, was too difficult to comprehend. The decision to make a film about the degeneration of youth reflected contemporary concerns in 1969; the New Hollywood movement was creating a great number of films that depicted the sexuality and rebelliousness of young people.[140] A Clockwork Orange was shot over 1970–1971 on a budget of £2 million.[141] Kubrick abandoned his use of CinemaScope in filming, deciding that the 1.66:1 widescreen format was, in the words of Baxter, an "acceptable compromise between spectacle and intimacy", and favored his "rigorously symmetrical framing", which "increased the beauty of his compositions".[142] The film heavily features "pop erotica" of the period, including a large white plastic set of male genitals, decor which Kubrick had intended to give it a "slightly futuristic" look.[143] McDowell's role in Lindsay Anderson's if.... (1968) was crucial to his casting as Alex,[x] and Kubrick professed that he probably would not have made the film if McDowell had been unavailable.[145] The film marked Kubrick's first collaboration with Wendy Carlos, who provided electronic renditions of Henry Purcell's Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary and Beethoven's "Ode to Joy".[146]

Because of its depiction of teenage violence, A Clockwork Orange became one of the most controversial films of its time, and part of an ongoing debate about violence and its glorification in cinema. It received an X rating, or certificate, in both the UK and US, on its release just before Christmas 1971, though many critics saw much of the violence depicted in the film as satirical, and less violent than Straw Dogs, which had been released a month earlier.[147] Kubrick personally pulled the film from release in the United Kingdom after receiving death threats following a series of copycat crimes based on the film; it was thus completely unavailable legally in the UK until after Kubrick's death, and not re-released until 2000.[148][y] John Trevelyan, the censor of the film, personally considered A Clockwork Orange to be "perhaps the most brilliant piece of cinematic art I've ever seen," and believed it to present an "intellectual argument rather than a sadistic spectacle" in its depiction of violence, but acknowledged that many would not agree.[150] Negative media hype over the film notwithstanding, A Clockwork Orange received four Academy Award nominations, for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Screenplay and Best Editing, and was named by the New York Film Critics Circle as the Best Film of 1971.[151] After William Friedkin won Best Director for The French Connection that year, he told the press: "Speaking personally, I think Stanley Kubrick is the best American film-maker of the year. In fact, not just this year, but the best, period."[152]

Period and horror filming (1972–1980)

Barry Lyndon

Barry Lyndon (1975) is an adaptation of William Makepeace Thackeray's The Luck of Barry Lyndon, a picaresque novel about the adventures of an 18th-century Irish rogue and social climber. John Calley of Warner Bros. agreed in 1972 to invest $2.5 million into the film, on condition that Kubrick approach major Hollywood stars, to ensure success.[153] Like previous films, Kubrick and his art department conducted an enormous amount of research on the 18th century. Extensive photographs were taken of locations and artwork in particular, and paintings were meticulously replicated from works of the great masters of the period in the film.[154][z] The film was shot on location in Ireland, beginning in the autumn of 1973, at a cost of $11 million with a cast and crew of 170.[156] The decision to shoot in Ireland stemmed from the fact that it still retained many buildings from the 18th century period which England lacked.[157] The production was problematic from the start, plagued with heavy rain and political strife involving Northern Ireland at the time.[158] After Kubrick received death threats from the IRA in 1974 due to the shooting scenes with English soldiers, he fled Ireland with his family on a ferry from Dún Laoghaire under an assumed identity and resumed filming in England.[159]

Baxter notes that Barry Lyndon was the film which made Kubrick notorious for paying scrupulous attention to detail, often demanding twenty or thirty retakes of the same scene to perfect his art.[160] Often considered to be his most authentic-looking picture,[161] the cinematography and lighting techniques that Kubrick and cinematographer John Alcott used in Barry Lyndon were highly innovative. Interior scenes were shot with a specially adapted high-speed f/0.7 Zeiss camera lens originally developed for NASA to be used in satellite photography. The lenses allowed many scenes to be lit only with candlelight, creating two-dimensional, diffused-light images reminiscent of 18th-century paintings.[162] Cinematographer Allen Daviau states that the method gives the audience a way of seeing the characters and scenes as they would have been seen by people at the time.[163] Many of the fight scenes were shot with a hand-held camera to produce a "sense of documentary realism and immediacy".[164]

Barry Lyndon found a great audience in France, but was a box office failure, grossing just $9.5 million in the American market, not even close to the $30 million Warner Bros. needed to generate a profit.[165] The pace and length of Barry Lyndon at three hours put off many American critics and audiences, but the film was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won four, including Best Art Direction, Best Cinematography, Best Costume Design, and Best Musical Score, more than any other Kubrick film. As with most of Kubrick's films, Barry Lyndon's reputation has grown through the years and it is now considered to be one of his best, particularly among filmmakers and critics. Numerous polls, such as The Village Voice (1999),[166] Sight & Sound (2002),[167] and Time (2005),[168] have rated it as one of the greatest films ever made. As of March 2019[update], it has a 94% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 64 reviews.[169] Ebert referred to it as "one of the most beautiful films ever made ... certainly in every frame a Kubrick film: technically awesome, emotionally distant, remorseless in its doubt of human goodness".[170]

The Shining

The Shining, released in 1980, was adapted from the novel of the same name by Stephen King. The film stars Jack Nicholson as a writer who takes a job as a winter caretaker of an isolated hotel in the Rocky Mountains. He spends the winter there with his wife, played by Shelley Duvall, and their young son, who displays paranormal abilities. During their stay, they confront both Jack's descent into madness and apparent supernatural horrors lurking in the hotel. Kubrick gave his actors freedom to extend the script and even improvise on occasion, and as a result, Nicholson was responsible for the 'Here's Johnny!' line and the scene in which he's sitting at the typewriter and unleashes his anger upon his wife.[171] Kubrick often demanded up to 70 or 80 retakes of the same scene. Duvall, whom Kubrick intentionally isolated and argued with, was forced to perform the exhausting baseball bat scene 127 times.[172] The bar scene with the ghostly bartender was shot 36 times, while the kitchen scene between the characters of Danny (Danny Lloyd) and Halloran (Scatman Crothers) ran to 148 takes.[173] The aerial shots of the Overlook Hotel were shot at Timberline Lodge on Mount Hood in Oregon, while the interiors of the hotel were shot at Elstree Studios in England between May 1978 and April 1979.[174] Cardboard models were made of all of the sets of the film, and the lighting of them was a massive undertaking, which took four months of electrical wiring.[175] Kubrick made extensive use of the newly invented Steadicam, a weight-balanced camera support, which allowed for smooth hand-held camera movement in scenes where a conventional camera track was impractical. According to Garrett Brown, Steadicam's inventor, it was the first picture to use its full potential.[176] The Shining was not the only horror film to which Kubrick had been linked; he had turned down the directing of both The Exorcist (1973) and Exorcist II: The Heretic (1977), despite once saying in 1966 to a friend that he had long desired to "make the world's scariest movie, involving a series of episodes that would play upon the nightmare fears of the audience".[177] Kubrick worked again with Carlos, who provided an electronic version of the Dies Irae segment from Hector Berlioz's "Symphonie fantastique".

Five days after release on May 23, 1980, Kubrick ordered the deletion of a final scene, in which the hotel manager Ullman (Barry Nelson) visits Wendy (Shelley Duvall) in hospital, believing it unnecessary after witnessing the audience excitement in cinemas at the film's climax.[178] The Shining opened to strong box office takings, earning $1 million on the first weekend and earning $30.9 million in America by the end of the year.[174] The original critical response was mixed, and King detested the film and disliked Kubrick.[179] The Shining is now considered to be a horror classic,[180] and the American Film Institute ranked it as the 29th greatest thriller film of all time in 2001.[181]

Later work and final years (1981–1999)

Full Metal Jacket

Kubrick met author Michael Herr through mutual friend David Cornwell (novelist John le Carré) in 1980, and became interested in his book Dispatches, about the Vietnam War.[182] Herr had recently written Martin Sheen's narration for Apocalypse Now (1979). Kubrick was also intrigued by Gustav Hasford's Vietnam War novel The Short-Timers. With the vision in mind to shoot what would become Full Metal Jacket (1987), Kubrick began working with both Herr and Hasford separately on a script. He eventually found Hasford's novel to be "brutally honest" and decided to shoot a film which closely follows the novel.[182] All of the film was shot at a cost of $17 million within a 30-mile radius of his house between August 1985 and September 1986, later than scheduled as Kubrick shut down production for five months following a near-fatal accident with a jeep involving Lee Ermey.[183] A derelict gasworks in Beckton in the London Docklands area posed as the ruined city of Huế,[184] which makes the film visually very different from other Vietnam War films. Around 200 palm trees were imported via 40-foot trailers by road from North Africa, at a cost of £1000 a tree, and thousands of plastic plants were ordered from Hong Kong to provide foliage for the film.[185] Kubrick explained he made the film look realistic by using natural light, and achieved a "newsreel effect" by making the Steadicam shots less steady, [186] which reviewers and commentators thought contributed to the bleakness and seriousness of the film.[187]

According to critic Michel Ciment, the film contained some of Kubrick's trademark characteristics, such as his selection of ironic music, portrayals of men being dehumanized, and attention to extreme detail to achieve realism. In a later scene, United States Marines patrol the ruins of an abandoned and destroyed city singing the theme song to the Mickey Mouse Club as a sardonic counterpoint.[188] The film opened strongly in June 1987, taking over $30 million in the first 50 days alone,[189] but critically it was overshadowed by the success of Oliver Stone's Platoon, released a year earlier.[190] Co-star Matthew Modine stated one of Kubrick's favorite reviews read: "The first half of FMJ is brilliant. Then the film degenerates into a masterpiece."[191] Ebert was not particularly impressed with it, awarding it a mediocre 2.5 out of 4. He concluded: "Stanley Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket is more like a book of short stories than a novel", a "strangely shapeless film from the man whose work usually imposes a ferociously consistent vision on his material".[192]

Eyes Wide Shut

Kubrick's final film was Eyes Wide Shut (1999), starring Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman as a Manhattan couple on a sexual odyssey. Tom Cruise portrays a doctor who witnesses a bizarre masked quasireligious orgiastic ritual at a country mansion, a discovery which later threatens his life. The story is based on Arthur Schnitzler's 1926 Freudian novella Traumnovelle (Dream Story in English), which Kubrick relocated from turn-of-the-century Vienna to New York City in the 1990s. Kubrick said of the novel: "A difficult book to describe—what good book isn't. It explores the sexual ambivalence of a happy marriage and tries to equate the importance of sexual dreams and might-have-beens with reality. All of Schnitzler's work is psychologically brilliant".[193] Kubrick was almost 70, but worked relentlessly for 15 months to get the film out by its planned release date of July 16, 1999. He commenced a script with Frederic Raphael,[164] and worked 18 hours a day, while maintaining complete confidentiality about the film.[194]

Eyes Wide Shut, like Lolita and A Clockwork Orange before it, faced censorship before release. Kubrick sent an unfinished preview copy to the stars and producers a few months before release, but his sudden death on March 7, 1999, came a few days after he finished editing. He never saw the final version released to the public,[195] but he did see the preview of the film with Warner Bros., Cruise, and Kidman, and had reportedly told Warner executive Julian Senior that it was his "best film ever".[196] At the time, critical opinion of the film was mixed, and it was viewed less favorably than most of Kubrick's films. Ebert awarded it 3.5 out of 4 stars, comparing the structure to a thriller and writing that it is "like an erotic daydream about chances missed and opportunities avoided", and thought that Kubrick's use of lighting at Christmas made the film "all a little garish, like an urban sideshow".[197] Stephen Hunter of The Washington Post disliked the film, writing that it "is actually sad, rather than bad. It feels creaky, ancient, hopelessly out of touch, infatuated with the hot taboos of his youth and unable to connect with that twisty thing contemporary sexuality has become."[198]

Unfinished and unrealized projects

A.I. Artificial Intelligence

Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, Kubrick collaborated with Brian Aldiss on expanding his short story "Supertoys Last All Summer Long" into a three-act film. It was a futuristic fairy tale about a robot that resembles and behaves as a child, and his efforts to become a 'real boy' in a manner similar to Pinocchio. Kubrick approached Steven Spielberg in 1995 with the AI script with the possibility of Steven Spielberg directing it and Kubrick producing it.[190] Kubrick reportedly held long telephone discussions with Spielberg regarding the film, and, according to Spielberg, at one point stated that the subject matter was closer to Spielberg's sensibilities than his.[199]

Following Kubrick's sudden death in 1999, Spielberg took the drafts and notes left by Kubrick and his writers and composed a new screenplay based on an earlier 90-page story treatment by Ian Watson written under Kubrick's supervision and specifications.[200] In association with what remained of Kubrick's production unit, he directed the film A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001)[200][201] which was produced by Kubrick's longtime producer (and brother-in-law) Jan Harlan.[202] Sets, costumes, and art direction were based on the works of conceptual artist Chris Baker, who had also done much of his work under Kubrick's supervision.[203]

Spielberg was able to function autonomously in Kubrick's absence, but said he felt "inhibited to honor him", and followed Kubrick's visual schema with as much fidelity as he could. Spielberg, who once referred to Kubrick as "the greatest master I ever served", now with production underway, admitted, "I felt like I was being coached by a ghost."[204] The film was released in June 2001. It contains a posthumous production credit for Stanley Kubrick at the beginning and the brief dedication "For Stanley Kubrick" at the end. John Williams's score contains many allusions to pieces heard in other Kubrick films.[205]

Napoleon

Following 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick planned to make a film about the life of Napoleon. Fascinated by the French leader's life and "self-destruction",[206] Kubrick spent a great deal of time planning the film's development and conducted about two years of research into Napoleon's life, reading several hundred books and gaining access to his personal memoirs and commentaries. He tried to see every film about Napoleon and found none of them appealing, including Abel Gance's 1927 film which is generally considered to be a masterpiece, but for Kubrick, a "really terrible" movie.[207] LoBrutto states that Napoleon was an ideal subject for Kubrick, embracing Kubrick's "passion for control, power, obsession, strategy, and the military", while Napoleon's psychological intensity and depth, logistical genius and war, sex, and the evil nature of man were all ingredients which deeply appealed to Kubrick.[208]

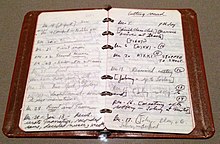

Kubrick drafted a screenplay in 1961, and envisaged making a "grandiose" epic, with up to 40,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry. He intended hiring the armed forces of an entire country to make the film, as he considered Napoleonic battles to be "so beautiful, like vast lethal ballets", with an "aesthetic brilliance that doesn't require a military mind to appreciate". He wanted them replicated as authentically as possible on screen.[209] Kubrick sent research teams to scout for locations across Europe, and commissioned screenwriter and director Andrew Birkin, one of his young assistants on 2001, to the Isle of Elba, Austerlitz, and Waterloo, taking thousands of pictures for his later perusal. Kubrick approached numerous stars to play leading roles, including Audrey Hepburn for Empress Josephine, a part which she could not accept due to semiretirement.[210] British actors David Hemmings and Ian Holm were considered for the lead role of Napoleon, before Jack Nicholson was cast.[211] The film was well into preproduction and ready to begin filming in 1969 when MGM canceled the project. Numerous reasons have been cited for the abandonment of the project, including its projected cost, a change of ownership at MGM,[206] and the poor reception that the 1970 Soviet film about Napoleon, Waterloo, received. In 2011, Taschen published the book Stanley Kubrick's Napoleon: The Greatest Movie Never Made, a large volume compilation of literature and source documents from Kubrick, such as scene photo ideas and copies of letters Kubrick wrote and received. In March 2013, Steven Spielberg, who previously collaborated with Kubrick on A.I. Artificial Intelligence and is a passionate admirer of his work, announced that he would be developing Napoleon as a TV miniseries based on Kubrick's original screenplay.[212]

Other projects

In the 1950s, Kubrick and Harris developed a sitcom starring Ernie Kovacs and a film adaption of the book I Stole $16,000,000, but nothing came of them.[71] Tony Frewin, an assistant who worked with the director for a long period of time, revealed in a 2013 Atlantic article: "[Kubrick] was limitlessly interested in anything to do with Nazis and desperately wanted to make a film on the subject." Kubrick had intended to make a film about Dietrich Schulz-Köhn, a Nazi officer who used the pen name "Dr. Jazz" to write reviews of German music scenes during the Nazi era. Kubrick had been given a copy of the Mike Zwerin book Swing Under the Nazis after he had finished production on Full Metal Jacket, the front cover of which featured a photograph of Schulz-Köhn. A screenplay was never completed and Kubrick's adaptation was never initiated.[213] The unfinished Aryan Papers, based on Louis Begley's debut novel Wartime Lies, was a factor in the abandonment of the project. Work on Aryan Papers depressed Kubrick enormously, and he eventually decided that Steven Spielberg's Schindler's List (1993) covered much of the same material.[190]

According to biographer John Baxter, Kubrick had shown an interest in directing a pornographic film based on a satirical novel written by Terry Southern, titled Blue Movie, about a director who makes Hollywood's first big-budget porn film. Baxter claims that Kubrick concluded he did not have the patience or temperament to become involved in the porn industry, and Southern stated that Kubrick was "too ultra conservative" towards sexuality to have gone ahead with it, but liked the idea.[214] Kubrick was unable to direct a film of Umberto Eco's Foucault's Pendulum as Eco had given his publisher instructions to never sell the film rights to any of his books after his dissatisfaction with the film version of The Name of the Rose.[215] Also, when the film rights to Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings were sold to United Artists, the Beatles approached Kubrick to direct them in a film adaptation, but Kubrick was unwilling to produce a film based on a very popular book.[216]

Career influences

Anyone who has ever been privileged to direct a film knows that, although it can be like trying to write War and Peace in a bumper car at an amusement park, when you finally get it right, there are not many joys in life that can equal the feeling.

— Stanley Kubrick, accepting the D. W. Griffith Award[217]

As a young man, Kubrick was fascinated by the films of Soviet filmmakers such as Sergei Eisenstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin.[218] Kubrick read Pudovkin's seminal theoretical work, Film Technique, which argues that editing makes film a unique art form, and it needs to be employed to manipulate the medium to its fullest. Kubrick recommended this work to others for many years. Thomas Nelson describes this book as "the greatest influence of any single written work on the evolution of [Kubrick's] private aesthetics". Kubrick also found the ideas of Konstantin Stanislavski to be essential to his understanding the basics of directing, and gave himself a crash course to learn his methods.[219]

Kubrick's family and many critics felt that his Jewish ancestry may have contributed to his worldview and aspects of his films. After his death, both his daughter and wife stated that he was not religious, but "did not deny his Jewishness, not at all". His daughter noted that he wanted to make a film about the Holocaust, the Aryan Papers, having spent years researching the subject.[220] Most of Kubrick's friends and early photography and film collaborators were Jewish, and his first two marriages were to daughters of recent Jewish immigrants from Europe. British screenwriter Frederic Raphael, who worked closely with Kubrick in his final years, believes that the originality of Kubrick's films was partly because he "had a (Jewish?) respect for scholars". He declared that it was "absurd to try to understand Stanley Kubrick without reckoning on Jewishness as a fundamental aspect of his mentality".[221] Walker notes that Kubrick was influenced by the tracking and "fluid camera" styles of director Max Ophüls, and used them in many of his films, including Paths of Glory and 2001: A Space Odyssey. Kubrick noted how in Ophüls' films "the camera went through every wall and every floor".[222] He once named Ophüls' Le Plaisir (1952) as his favorite film. According to film historian John Wakeman, Ophüls himself learned the technique from director Anatole Litvak in the 1930s, when he was his assistant, and whose work was "replete with the camera trackings, pans and swoops which later became the trademark of Max Ophüls".[223] Geoffrey Cocks believes that Kubrick was also influenced by Ophüls' stories of thwarted love and a preoccupation with predatory men, while Herr notes that Kubrick was deeply inspired by G. W. Pabst, who earlier tried, but was unable to adapt Schnitzler's Traumnovelle, the basis of Eyes Wide Shut.[224] Film historian/critic Robert Kolker sees the influence of Orson Welles' moving camera shots on Kubrick's style. LoBrutto notes that Kubrick identified with Welles and that this influenced the making of The Killing, with its "multiple points of view, extreme angles, and deep focus".[225][226]

Kubrick admired the work of Ingmar Bergman and expressed it in personal letter: "Your vision of life has moved me deeply, much more deeply than I have ever been moved by any films. I believe you are the greatest film-maker at work today [...], unsurpassed by anyone in the creation of mood and atmosphere, the subtlety of performance, the avoidance of the obvious, the truthfulness and completeness of characterization. To this one must also add everything else that goes into the making of a film; [...] and I shall look forward with eagerness to each of your films."[227]

When the American magazine Cinema asked Kubrick in 1963 to name his favorite films, he listed Federico Fellini's I Vitelloni as number one in his Top 10 list.[228]

Directing techniques

Philosophy

Kubrick's films typically involve expressions of an inner struggle, examined from different perspectives.[217] He was very careful not to present his own views of the meaning of his films and to leave them open to interpretation. He explained in a 1960 interview with Robert Emmett Ginna:

"One of the things I always find extremely difficult, when a picture's finished, is when a writer or a film reviewer asks, 'Now, what is it that you were trying to say in that picture?' And without being thought too presumptuous for using this analogy, I like to remember what T. S. Eliot said to someone who had asked him—I believe it was The Waste Land—what he meant by the poem. He replied, 'I meant what I said.' If I could have said it any differently, I would have".[229]

Kubrick likened the understanding of his films to popular music, in that whatever the background or intellect of the individual, a Beatles record, for instance, can be appreciated both by the Alabama truck driver and the young Cambridge intellectual, because their "emotions and subconscious are far more similar than their intellects". He believed that the subconscious emotional reaction experienced by audiences was far more powerful in the film medium than in any other traditional verbal form, and this was one of the reasons why he often relied on long periods in his films without dialogue, placing emphasis on images and sound.[229] In a 1975 Time magazine interview, Kubrick further stated: "The essence of a dramatic form is to let an idea come over people without it being plainly stated. When you say something directly, it is simply not as potent as it is when you allow people to discover it for themselves."[40] He also said: "Realism is probably the best way to dramatize argument and ideas. Fantasy may deal best with themes which lie primarily in the unconscious".[230]

Diane Johnson, who co-wrote the screenplay for The Shining with Kubrick, notes that he "always said that it was better to adapt a book rather than write an original screenplay, and that you should choose a work that isn't a masterpiece so you can improve on it. Which is what he's always done, except with Lolita".[231] When deciding on a subject for a film, there were many aspects that he looked for, and he always made films which would "appeal to every sort of viewer, whatever their expectation of film".[232] According to his co-producer Jan Harlan, Kubrick mostly "wanted to make films about things that mattered, that not only had form, but substance".[233] Kubrick believed that audiences quite often were attracted to "enigmas and allegories" and did not like films in which everything was spelled out clearly.[234]

Sexuality in Kubrick's films is usually depicted outside matrimonial relationships in hostile situations. Baxter states that Kubrick explores the "furtive and violent side alleys of the sexual experience: voyeurism, domination, bondage and rape" in his films.[235] He further points out that films like A Clockwork Orange are "powerfully homoerotic", from Alex walking about his parents' flat in his Y-fronts, one eye being "made up with doll-like false eyelashes", to his innocent acceptance of the sexual advances of his post-corrective adviser Deltroid (Aubrey Morris).[236] Indeed, the film is thought to have been strongly influenced by Kubrick's many viewings of Matsumoto Toshio's 1969 landmark in queer cinema, Funeral Parade of Roses.[237] Film critic Adrian Turner notes that Kubrick's films appear to be "preoccupied with questions of universal and inherited evil", and Malcolm McDowell referred to his humor as "black as coal", questioning his outlook on humanity.[238] A few of his pictures were obvious satires and black comedies, such as Lolita and Dr. Strangelove; many of his other films also contained less visible elements of satire or irony. His films are unpredictable, examining "the duality and contradictions that exist in all of us".[239] Ciment notes how Kubrick often tried to confound audience expectations by establishing radically different moods from one film to the next, remarking that he was almost "obsessed with contradicting himself, with making each work a critique of the previous one".[240] Kubrick stated that "there is no deliberate pattern to the stories that I have chosen to make into films. About the only factor at work each time is that I try not to repeat myself".[241] As a result, Kubrick was often misunderstood by critics, and only once did he have unanimously positive reviews upon the release of a film—for Paths of Glory.[242]

Writing and staging scenes

Film author Patrick Webster considers Kubrick's methods of writing and developing scenes to fit with the classical auteur theory of directing, allowing collaboration and improvisation with the actors during filming.[243] Malcolm McDowell recalled Kubrick's collaborative emphasis during their discussions and his willingness to allow him to improvise a scene, stating that "there was a script and we followed it, but when it didn't work he knew it, and we had to keep rehearsing endlessly until we were bored with it".[244] Once Kubrick was confident in the overall staging of a scene, and felt the actors were prepared, he would then develop the visual aspects, including camera and lighting placement. Walker believes that Kubrick was one of "very few film directors competent to instruct their lighting photographers in the precise effect they want".[245] Baxter believes that Kubrick was heavily influenced by his ancestry and always possessed a European perspective to filmmaking, particularly the Austro-Hungarian empire and his admiration for Max Ophuls and Richard Strauss.[246]

Gilbert Adair, writing in a review for Full Metal Jacket, commented that "Kubrick's approach to language has always been of a reductive and uncompromisingly deterministic nature. He appears to view it as the exclusive product of environmental conditioning, only very marginally influenced by concepts of subjectivity and interiority, by all whims, shades and modulations of personal expression".[247] Johnson notes that although Kubrick was a "visual filmmaker", he also loved words and was like a writer in his approach, very sensitive to the story itself, which he found unique.[248] Before shooting began, Kubrick tried to have the script as complete as possible, but still allowed himself enough space to make changes during the filming, finding it "more profitable to avoid locking up any ideas about staging or camera or even dialogue prior to rehearsals" as he put it.[245] Kubrick told Robert Emmett Ginna: "I think you have to view the entire problem of putting the story you want to tell up there on that light square. It begins with the selection of the property; it continues through the creation of the story, the sets, the costumes, the photography and the acting. And when the picture is shot, it's only partially finished. I think the cutting is just a continuation of directing a movie. I think the use of music effects, opticals and finally main titles are all part of telling the story. And I think the fragmentation of these jobs, by different people, is a very bad thing".[161] Kubrick also said: "I think that the best plot is no apparent plot. I like a slow start, the start that gets under the audience's skin and involves them so that they can appreciate grace notes and soft tones and don't have to be pounded over the head with plot points and suspense tools."[156]

In terms of Kubrick's screenwriting and narratives, posthumous analysis of his films often highlight a pervasive "misanthropy", an unsentimental style, and being less interested in the specific emotions or personality traits of his characters.[249] Filmmaker Quentin Tarantino describes the manner in which Kubrick writes characters and films as "cold" and detached.[250]

Directing style

They work with Stanley and go through hells that nothing in their careers could have prepared them for, they think they must have been mad to get involved, they think that they'd die before they would ever work with him again, that fixated maniac; and when it's all behind them and the profound fatigue of so much intensity has worn off, they'd do anything in the world to work for him again. For the rest of their professional lives they long to work with someone who cared the way Stanley did, someone they could learn from. They look for someone to respect the way they'd come to respect him, but they can never find anybody ... I've heard this story so many times.

Multiple takes

Kubrick was notorious for filming far more takes than is common during feature production and his relentless approach often placed large demands on his actors. Jack Nicholson remarked that Kubrick would frequently require up to fifty takes of a scene before the director felt justice had been done to the material.[252] Nicole Kidman explained that the dozens of takes he often required had the effect of suppressing an actor's conscious thoughts about technique, diffusing the concentration Kubrick said he could see in the eyes of an actor who was not yet performing at the peak of their ability and helping them to enter a "deeper place".[253] Kubrick echoed this sentiment, saying, "[a]ctors are essentially emotion-producing instruments, and some are always tuned and ready while others will reach a fantastic pitch on one take and never equal it again, no matter how hard they try".[254]

While Kubrick's high take ratio was considered by some critics to be irrational he firmly believed that actors were at their best during filming, as opposed to in rehearsals, saying, "[w]hen you make a movie, it takes a few days just to get used to the crew, because it is like getting undressed in front of fifty people. Once you're accustomed to them, the presence of even one other person on set is discordant and tends to produce self-consciousness in the actors, and certainly in itself".[255][256]

In 1987, when Kubrick was asked about his reputation for excessive takes by Rolling Stone, he replied that it was exaggerated but that when it was true, "[i]t happens when actors are unprepared. You cannot act without knowing dialogue. If actors have to think about the words, they can't work on the emotion. So you end up doing thirty takes of something. And still you can see the concentration in their eyes; they don't know their lines. So you just shoot it and shoot it and hope you can get something out of it in pieces."[257] He likewise told biographer Michel Ciment that, "[a]n actor can only do one thing at a time, and when he learned his lines only well enough to say them while he's thinking about them, he will always have trouble as soon as he has to work on the emotions of the scene or find camera marks. In a strong emotional scene, it is always best to be able to shoot in complete takes to allow the actor a continuity of emotion, and it is rare for most actors to reach their peak more than once or twice. There are, occasionally, scenes which benefit from extra takes, but even then, I'm not sure that the early takes aren't just glorified rehearsals with the adding adrenaline of film running through the camera."[258]

Matthew Modine, who played Joker in Full Metal Jacket, echoes these assessments of even a world-renowned actor's delivery on a Kubrick film. In an oral history gathered by Peter Bogdanovich after the director's death Modine recalled that, "I once asked [Kubrick] why he so often did a lot of takes. [...] And he talked about Jack Nicholson [saying] ''Jack would come in during the blocking and he kind of fumbled through the lines. He'd be learning them while he was there. And then you'd start shooting and after take 3 or take 4 or take 5 you'd get the Jack Nicholson that everybody knows and most directors would be happy with. And then you'd go up to 10 or 15 and he'd be really awful and then he'd start to understand what the lines were, what the lines meant, and then he'd become unconscious about what he was saying. So by take 30 or take 40 the lines became something else.''[259]

By contrast, during the filming of Full Metal Jacket the former Marine Corps drill instructor R. Lee Ermey often satisfied Kubrick in as few as two or three takes. The director praised Ermey as an excellent performer, later saying to Rolling Stone that Ermey's intense familiarity with the role had perfected his delivery and fluency of improvisation to a level he could not have hoped to discover in a professional actor, no matter how many takes they were given.[257] Kubrick repeated his praise to the Washington Post, saying he had, "always found that some people can act and some can't, whether or not they've had training. And I suspect that being a drill instructor is, in a sense, being an actor. Because they're saying the same things every eight weeks, to new guys, like they're saying it for the first time – and that's acting."[260]

Discussions with actors

On set, Kubrick would devote his personal breaks to lengthy discussions with his actors. Among those who valued his attention was Tony Curtis, star of Spartacus, who said Kubrick was his favorite director, adding, "his greatest effectiveness was his one-on-one relationship with actors."[94] He further added, "Kubrick had his own approach to film-making. He wanted to see the actor's faces. He didn't want cameras always in a wide shot twenty-five feet away, he wanted close-ups, he wanted to keep the camera moving. That was his style."[85] Similarly, Malcolm McDowell recalls the long discussions he had with Kubrick to help him develop his character in A Clockwork Orange, noting that on set he felt entirely uninhibited and free, which is what made Kubrick "such a great director".[252] Kubrick also allowed actors at times to improvise and to "break the rules", particularly with Peter Sellers in Lolita, which became a turning point in his career as it allowed him to work creatively during the shooting, as opposed to the preproduction stage.[261] During an interview, Ryan O'Neal recalled Kubrick's directing style: "God, he works you hard. He moves you, pushes you, helps you, gets cross with you, but above all he teaches you the value of a good director. Stanley brought out aspects of my personality and acting instincts that had been dormant ... My strong suspicion [was] that I was involved in something great".[262] He further added that working with Kubrick was "a stunning experience" and that he never recovered from working with somebody of such magnificence.[263]

Cinematography

Kubrick credited the ease with which he filmed scenes to his early years as a photographer.[264] He rarely added camera instructions in the script, preferring to handle that after a scene is created, as the visual part of film-making came easiest to him.[265] Even when deciding which props and settings would be used, Kubrick paid meticulous attention to detail and tried to collect as much background material as possible, activities the director likened to being "a detective".[266] Cinematographer John Alcott, who worked closely with Kubrick on four of his films, and won an Oscar for Best Cinematography on Barry Lyndon, remarked that Kubrick "questions everything",[267] and was involved in the technical aspects of film-making including camera placement, scene composition, choice of lens, and even operating the camera which would usually be left to the cinematographer. Alcott considered Kubrick to be the "nearest thing to genius I've ever worked with, with all the problems of a genius".[268]